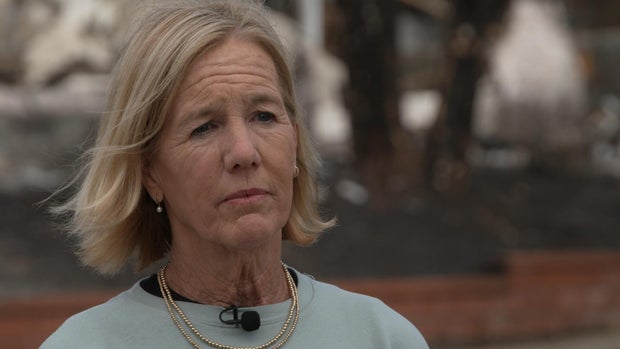

Lynn McIntyre is supposed to feel like one of the lucky ones. When a series of wildfires devastated Los Angeles in January, her Pacific Palisades home was among those inexplicably spared. But with every single home around her burned to the ground, McIntyre calls herself something different: “one of the left behinds.”

“I don’t feel as lucky as people think,” she said. “Because I don’t have the same set of issues that all of my neighbors have. They’re cut and dried.”

Cut and dried, she says, because their homes are total losses in the eyes of insurance companies. They don’t have to figure out how to clean up a home that’s standing in a sea of toxic ash, soot and debris, the remnants of all the synthetic stuff that makes up modern life – appliances, clothing and carpets — after it all burned at high heat.

“There’s no guidelines for what you should be looking for. There’s no guidelines telling you who to call or regulate testing,” she said. “It’s a Wild West out there with the testing, with the remediation companies. People are just grasping at straws with no guidance from government.”

Tests, which McIntyre says she spent more than $5,000 of her own money on, showed arsenic was present inside her home as well as lead levels 22 times higher than what’s considered safe by the EPA.

60 Minutes

Still, McIntyre’s insurer has told her it will not cover the cost of cleaning up her home because it does not constitute a “direct physical loss.” She also won’t get help from the agencies tasked by the Federal Emergency Management Agency with cleaning up from the fires – the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The first phase of cleaning up Los Angeles

The EPA started its portion of the cleanup, known as Phase 1, first by removing all the hazardous waste – things like propane tanks, cleaning supplies and paint cans – and combing the burn zones for electric vehicles, the newest challenge when cleaning up after an urban fire.

Electric vehicles are powered by lithium-ion batteries, which can explode, emit toxic gasses or re-ignite even weeks or months after they’ve been damaged. Just one electric vehicle contains thousands of those batteries. Chris Myers, who leads the EPA’s Lithium-Ion Battery Emergency Response team, said leaving those “uncontrolled out in the field” poses a danger to the public.

“They are delicate, they are fragile, they’re unstable,” he explained. “In the public, access is very, very dangerous for anyone who is onsite, right, not just our workers, but the public at large.”

EPA teams found about 600 electric vehicles, most of them in McIntyre’s Palisades neighborhood.

But just identifying incinerated electric vehicles has been a challenge, according to Myers. So, the EPA conducted reconnaissance, sending dozens of teams across Altadena and the Pacific Palisades, searching for the skeletons of electric vehicles in the debris and calling power companies and manufacturers to locate the power walls, which were often attached to homes, to charge them.

60 Minutes

The instability of these damaged batteries means extracting them from a single electric vehicle can take a six-person team up to two hours. It’s a delicate surgery performed with heavy machinery. First, the top of the car is sawed off and then flipped over, exposing the battery underneath. The thousands of cells that make up the battery are scooped out and placed into steel drums which are transported to a temporary processing site. Once at the processing site they’re plunged into a saltwater solution for three days, a process that allows any trapped energy in the battery to dissipate, making them far less likely to reignite. Lastly, the batteries are shoveled onto a tarp and steamrolled, ensuring that what’s left, according to Myers, can no longer be considered a battery.

Handling California’s hazardous waste

So where does all that battery waste end up? 60 Minutes found the answer 600 miles away.

Despite no longer being considered “batteries,” what’s left is still technically considered a hazardous material under California’s strict environmental regulations. We learned that this battery waste was being trucked hundreds of miles away to a hazardous waste landfill – in Utah.

For years, the state of California has struggled to keep up with the amount of hazardous waste it generates. California only has two operating landfills certified to take hazardous materials and, even before the fires, those two sites couldn’t hold all of the state’s hazardous waste. Instead about half of it is trucked hundreds of miles away to nearby states, mostly Utah and Arizona, which rely on more lenient federal waste standards.

Removing billions of pounds of debris

After the EPA finished clearing more than 9,000 properties of hazardous debris and while that battery waste was still being hauled out of state, the second phase of the cleanup was getting underway. The second phase involves removing all the rest of the debris – about nine billion pounds’ worth – including everything from concrete foundations to furniture and contaminated soil.

This phase is being overseen by the U.S. Army Corps Engineers under the leadership of Col. Eric Swenson, who anticipates their work will be done by the first anniversary of the fires.

60 Minutes

It’s a task that’s being carried out parcel by parcel, dump truck by dump truck. Swenson said the time it takes to clear one property can take up to 10 days depending on the complexity of the structure and the terrain it sits on.

“If we have a house that’s pinned on the side of a mountain, pinned on the side of a coastline, those properties could take us six, eight, 10 days to do, because we’re gonna need some specialized equipment to get in there,” Swenson said.

The Army Corps and its cavalry of dump trucks is also responsible for removing six inches of topsoil from the charred properties once the debris is cleared. Swenson’s confident six inches is enough to make the soil safe again and worries that further excavation makes it difficult for homeowners to rebuild.

“All we’re doing is economically disadvantaging that owner, and delaying their ability to rebuild, ’cause now they’re gonna have to replace all of that soil we excavated– from– from that property,” Swenson said.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom doesn’t think removing six inches of soil is enough. His office asked FEMA, which determines the scope of work for the Army Corps, to test the remaining soil for toxic contaminants as it’s done after previous wildfires. FEMA says the agency changed its approach to soil testing in 2020 because it found that contamination deeper than six inches was typically pre-existing and not necessary for public health protection.

The long road home

But residents like Matthew Craig, who lived in Altadena, aren’t eligible for help from the Army Corps or EPA cleanup crews. Craig’s home, like Lynn McIntyre’s, is still standing, but the strong winds that fueled the wildfires pushed smoke and soot inside, leaving a fine layer of ash on everything. It’s that ash that worries him.

60 Minutes

“The house is filled with the ashes of thousands of homes that are hundreds of years old,” he said. “These houses are filled with asbestos. They’re filled with lead.”

Craig’s insurance company has agreed to test the inside of his home for toxins and he’s waiting to hear whether they’ll cover his clean up costs. Until testing can show that his home is safe, Craig says that he, his wife and young son won’t return.

McIntyre shares Craig’s concerns. She signed an 18-month lease on an apartment out of town, anticipating the road home for her, and her neighbors, will be a long one.

Clinton Mora is a reporter for Trending Insurance News. He has previously worked for the Forbes. As a contributor to Trending Insurance News, Clinton covers emerging a wide range of property and casualty insurance related stories.